Alright, I believe have found something of interest.

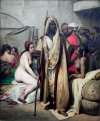

Two depictions of a woman tied to a native american torture/execution frame.

thanks for the pics, smilodontae. however i suppose it'd not be amiss to recall the remarkable torture-and-execution story of this brave natchez girl (from

executed today, under 1730th —

https://is.gd/a4YCyv):

1730: A Natchez woman tortured to death at New Orleans

Posted on 11 April, 2017 by Headsman

On this date in 1730, French-allied Tunica Indians put a captured Natchez woman to grisly public death under the walls of New Orleans.

Months earlier the Natchez had risen in rebellion against the colonists in Louisiana — a bloody settling of accounts the that answered a French push to colonize more land with an attack meant to drive them out of Louisiana altogether. The initial, surprise attacks slew 237 French subjects, many in stomach-turning fashion. Friend of the site Dr. Beachcombing details a particularly atrocious murder in his post on the affair at Beachcombing’s Bizarre History Blog.

So the French were in a state of rage and fright on April 10 — the day after Easter — when an allied tribe, the Tunica, showed up at the Big Easy with six Natchez captives in tow, three women and three children. Chief among them was a woman readily recognized by the French as the wife of a once-friendly Natchez chief now “known for being an enemy of the French.” Indeed, escapees from Natchez captivity slated her with having given the go-ahead for the torture-murder of three of their countrymen.

And this hated foe the Tunica proceeded to offer to the French, as a gesture of goodwill.

As Sophie White explains in her “Massacre, Mardi Gras, and Torture in Early New Orleans” (The William and Mary Quarterly, July 2013),* Louisiana territory governor Etienne Perier in slyly declining the prisoner intentionally condemned her to a speedy and spectacular death. Rather than taking her into official custody for disposal by the French judiciary or diplomatic organs, Perier put her up for a night in the French jail while her captors prepared a performance for the morrow calculated to slake the bloodlust of French and native alike.

White’s narrative is worth excerpting at length here; all the parentheticals come from White’s original text.

Officially, Governor Perier could claim that he had maintained French notions of justice by rejecting the Tunica offer of the prisoner of war (even though at a later date he would openly write of another four male and two female Natchez having “been burnt here”). Yet he allotted a space for the Tunica to torture her and arranged for her to be kept in jail overnight while the Tunica danced the black “calumet of death” in preparation for her execution. In the morning, after gathering firewood, erecting a frame, and painting their faces and bodies, the Tunica “began to run as if possessed by the devil and, while yelling (it is their custom), they ran to the jail where she was in chains”; she was engaged in a final assertion of sartorial self-preservation, “fixing a ribbon to her braided hair,” hair that she knew would soon be scalped.

Like Perier, the colonial populace also became involved in exacting revenge on this member of the Natchez nation. Not only were “all the Sauvages who were in New Orleans” present at the torture ritual but colonists also attended the performance as spectators, as they might in France attend a public execution. They watched as the Tunica tied her to a frame and as a Natchez man who had abandoned his kin and been adopted by the Tunica stepped forward to burn her, starting with “the hair [poil, or body hair] of her … then one breast, then the buttocks, then the left breast” (the ellipses represent a deliberate authorial omission on the part of Caillot). Commentators described the methodical burning of torture victims as a form of slow-cooking (“a petit feu”). For Caillot, the ritual burning of the victim’s genitals, breasts, and buttocks was marked by the carefully observed but gruesome sight of “the abundance of grease mixed with blood that ran onto the ground.” His description evoked the cooking of meat basted in fat, with the frame simulating a spit on which the victim was roasted; if this frame/spit did not physically turn its meat, the torturers made sure that she was evenly roasted on all sides by their methodical movement across her body. This food preparation imagery was followed by other cooking analogies. As they were about to kill her (in contrast to the procedure in France, where spectators waited for the execution to be complete before grabbing souvenir pieces of the criminal’s body), “the French women who had suffered at her hands at the Natchez [settlement] each took a sharpened cane and larded her,” just as French culinary techniques called for piercing meat with a sharp stick prior to the insertion of thin strips of lard.

The Natchez woman was not impressed, but “during that long and cruel torture never shed a tear. On the contrary, she seemed to deride the unskilfulness of her tormenters, insulting them, and threatening that her death would soon be avenged by her tribe.”

Over the next several years, the French not only turned back the attack but largely shattered and Natchez peoples, dispersing their remnants to fragmented communities throughout the U.S. South. Today only a few thousand Natchez souls remain, and their interesting language has died out entirely.

see also the note to the second picture (a generic depiction of the typical indigenous torture frame taken from jean-françois-benjamin dumont de montigny’s memoir): sophie white writes that this figure is identifiably female based on her genitalia and the long scalped hair mounted on the adjacent pole.

the very interesting from the point of view of our theme informative article by sophie white is on academia.edu (pdf):

https://is.gd/VSbNNE. the english translation of

The Memoir of Lieutenant Dumont, 1715–1747: A Sojourner in the French Atlantic see here:

https://is.gd/cPynzn.