Praefectus Praetorio

R.I.P. Brother of the Quill

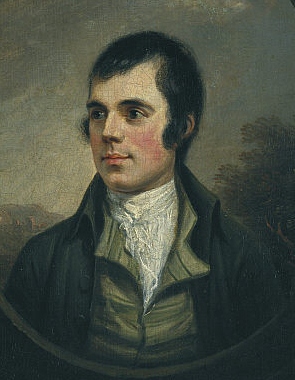

The Immortal Memory

Sad to say, on this 261st anniversary of the birth of Robert Burns, I have not arranged to attend a Burn’s Supper celebration. I, therefore, will not experience a learned expert in the life and work of the Scottish poet declaim a homage to “The Immortal Memory.”

In a meager and humble manner, I will give a few poor remarks here in honor of a man I greatly respect.

Robert Burns was born in Alloway, Ayrshire, Scotland, UK on January 25, 1759 and died in Dumfries, Scotland on July 21, 1796 at age 37.

I first became aware of the man when I was ten years old, in fifth grade. English Classes (Literature and composition – more American than English) in my school believed in the efficacy of young minds memorizing and reciting poetry. I had mixed feelings on this since I had a good memory and a love of poetry but was painfully shy and terrified of standing in front of the class. Nevertheless, confident in my memory and encouraged by my father’s ability to recite multiple pages of poetry he’d learned decades earlier, I volunteered to learn the most difficult poem on the proffered list, "To a Mouse, on Turning Her Up in Her Nest With the Plough, November, 1785."

The title alone should have been enough to scare me off. A medium-long poem of eight, six-line stanzas, written in the Lowland Scots-Language, it is little-known to most Americans, though the modern English translation of one line has become a cliché: “The best laid plans of mice and men go oft astray.” With a little help from my erudite father with the pronunciation (and the meaning of obscure Scots words), I proceeded to memorize the poem and deliver a recitation before the class which earned me rare praise from the English teacher, the apt-named Mr. Dickens. Throughout my life, I have often repeated in my mind (and even sometimes out loud for my own children) the rolling accented phrases of the opening lines:

Wee, sleekit, cowrin, tim'rous beastie,

O, what a pannic's in thy breastie!

(Little, cunning, cowering, timorous beast,

Oh, what a panic is in your breast!)

Robert (Rabbie) Burns, the National Bard, the Bard of Ayrshire, the Ploughman Poet, was the eldest of seven children of William Burns, an unschooled tenant farmer. Though William was known for his strength of character, he was consistently unsuccessful in life, migrating from farm to farm with his family. Raised in a life of poverty and hardship, Robert was mostly educated by his father. The severe manual labor of the farm left its traces in a premature stoop and a weakened constitution.

Early on, Rabbie had an eye for the lassies. When he was 15, he wrote his first known poem, "O, Once I Lov'd A Bonnie Lass" to Nelly Kilpatrick of the same age who worked in the fields with him. When he was 16, he was sent, briefly, to a tutor at Kirkoswald. There he met Peggy Thompson, 13, to whom he wrote two songs, "Now Westlin' Winds" and "I Dream'd I Lay".

Throughout his life Burns had affairs. His first child, Elizabeth "Bess" Burns (1785), was born to his mother's servant, Elizabeth Paton. Jean Armour, became pregnant with his twins in 1786. He married her, somewhat irregularly, in 1788 and she bore him nine children in eleven years, though only three survived infancy.

Burns, taking after his father was an indifferent farmer, but never stopped trying. His poetry was more successful, though the publishing and copyright systems of the time meant he made only a modest income there. And Rabbie, like his father was good at spending whatever came into his hands.

Burns always held liberal (for the day) political views and supported both the American and French revolutions as well as greater rights for the poor and universal (male) suffrage. These views caused him trouble with wealthy industrial sponsors. His anthem to universal brotherhood, "A Man's a Man for A' That" illustrates his outlook:

Then let us pray that come it may,

(As come it will for a' that,)

That Sense and Worth, o'er a' the earth,

Shall bear the gree, an' a' that.

For a' that, an' a' that,

It's coming yet for a' that,

That Man to Man, the world o'er,

Shall brothers be for a' that.

-

In addition to pure poetry, Burns researched Scottish folk melodies and wrote lyrics for many. Two of the most famous are “Auld Lang Syne” and "Scots Wha Hae." The latter served for a long time as an unofficial national anthem of the country.

By 1795, his long-standing rheumatic heart condition (possible aggravated by intemperance of life) caused his health to give way; he began to age prematurely and fell into fits of despondency. On the morning of 21 July 1796, Burns died in Dumfries, at the age of 37.

As with many a great spirit, the events of his life give only a scant glimpse into the greatness of his mind. For one of almost no formal education to write outstanding poetry in the Scots language, a light Scots dialect, and standard English, shows a great fluency of tongue. Whether calling for social justice, celebrating Scottish heritage, expressing tender or sensual love, having a rollicking funny time, or waxing philosophical, Burns was always in command of his subject.

On that note, I come to the peroration of the piece, the poem that first stirred my love for all things Burns. In his title, Burns dates it to November 1785 (his age, 26). Late Autumn plowing of a field, he overturns and destroys a mouse nest. Despite the fact that Burns bore it no ill-will, the rodent scurried off in terror at the rude attack. Burns observes that, without a snug nest, the wee creature might not survive the winter. As with the natural poetic mind, Burns began to muse on deeper issues. In fact, his brother claimed that the poet composed the entire poem while still holding his plough.

Burns waxes poetic on the poor mouse’s plans and efforts to prepare for winter and how Burns has destroyed them all. In his usual sense of brotherhood and social contract, he says the mouse is welcome to the small amount of grain he steals and says:

I'm truly sorry man's dominion,

Has broken nature's social union,

An' justifies that ill opinion,

Which makes thee startle

At me, thy poor, earth-born companion,

An' fellow-mortal!

After lamenting with the mouse that foresight and preparation may be in vain, Burn’s coins the phase I quoted first about the plans of mice and men.

But Mousie, thou art no thy-lane,

In proving foresight may be vain:

The best laid schemes o’ Mice an’ Men

Gang aft agley,

An’ lea’e us nought but grief an’ pain,

For promis’d joy!

But he doesn’t leave it there. Recalling the travails of his family growing up and presaging the difficulties ahead of him in the only ten years of life left him, Burns envies the mouse:

Still thou art blest, compar'd wi' me

The present only toucheth thee:

But, Och! I backward cast my e'e.

On prospects drear!

An' forward, tho' I canna see,

I guess an' fear!

Rest well today, Rabbie. Though your flame burned only briefly, it burned bright and has lit many a soul in the years you’ve been gone.

Sad to say, on this 261st anniversary of the birth of Robert Burns, I have not arranged to attend a Burn’s Supper celebration. I, therefore, will not experience a learned expert in the life and work of the Scottish poet declaim a homage to “The Immortal Memory.”

In a meager and humble manner, I will give a few poor remarks here in honor of a man I greatly respect.

Robert Burns was born in Alloway, Ayrshire, Scotland, UK on January 25, 1759 and died in Dumfries, Scotland on July 21, 1796 at age 37.

I first became aware of the man when I was ten years old, in fifth grade. English Classes (Literature and composition – more American than English) in my school believed in the efficacy of young minds memorizing and reciting poetry. I had mixed feelings on this since I had a good memory and a love of poetry but was painfully shy and terrified of standing in front of the class. Nevertheless, confident in my memory and encouraged by my father’s ability to recite multiple pages of poetry he’d learned decades earlier, I volunteered to learn the most difficult poem on the proffered list, "To a Mouse, on Turning Her Up in Her Nest With the Plough, November, 1785."

The title alone should have been enough to scare me off. A medium-long poem of eight, six-line stanzas, written in the Lowland Scots-Language, it is little-known to most Americans, though the modern English translation of one line has become a cliché: “The best laid plans of mice and men go oft astray.” With a little help from my erudite father with the pronunciation (and the meaning of obscure Scots words), I proceeded to memorize the poem and deliver a recitation before the class which earned me rare praise from the English teacher, the apt-named Mr. Dickens. Throughout my life, I have often repeated in my mind (and even sometimes out loud for my own children) the rolling accented phrases of the opening lines:

Wee, sleekit, cowrin, tim'rous beastie,

O, what a pannic's in thy breastie!

(Little, cunning, cowering, timorous beast,

Oh, what a panic is in your breast!)

Robert (Rabbie) Burns, the National Bard, the Bard of Ayrshire, the Ploughman Poet, was the eldest of seven children of William Burns, an unschooled tenant farmer. Though William was known for his strength of character, he was consistently unsuccessful in life, migrating from farm to farm with his family. Raised in a life of poverty and hardship, Robert was mostly educated by his father. The severe manual labor of the farm left its traces in a premature stoop and a weakened constitution.

Early on, Rabbie had an eye for the lassies. When he was 15, he wrote his first known poem, "O, Once I Lov'd A Bonnie Lass" to Nelly Kilpatrick of the same age who worked in the fields with him. When he was 16, he was sent, briefly, to a tutor at Kirkoswald. There he met Peggy Thompson, 13, to whom he wrote two songs, "Now Westlin' Winds" and "I Dream'd I Lay".

Throughout his life Burns had affairs. His first child, Elizabeth "Bess" Burns (1785), was born to his mother's servant, Elizabeth Paton. Jean Armour, became pregnant with his twins in 1786. He married her, somewhat irregularly, in 1788 and she bore him nine children in eleven years, though only three survived infancy.

Burns, taking after his father was an indifferent farmer, but never stopped trying. His poetry was more successful, though the publishing and copyright systems of the time meant he made only a modest income there. And Rabbie, like his father was good at spending whatever came into his hands.

Burns always held liberal (for the day) political views and supported both the American and French revolutions as well as greater rights for the poor and universal (male) suffrage. These views caused him trouble with wealthy industrial sponsors. His anthem to universal brotherhood, "A Man's a Man for A' That" illustrates his outlook:

Then let us pray that come it may,

(As come it will for a' that,)

That Sense and Worth, o'er a' the earth,

Shall bear the gree, an' a' that.

For a' that, an' a' that,

It's coming yet for a' that,

That Man to Man, the world o'er,

Shall brothers be for a' that.

-

In addition to pure poetry, Burns researched Scottish folk melodies and wrote lyrics for many. Two of the most famous are “Auld Lang Syne” and "Scots Wha Hae." The latter served for a long time as an unofficial national anthem of the country.

By 1795, his long-standing rheumatic heart condition (possible aggravated by intemperance of life) caused his health to give way; he began to age prematurely and fell into fits of despondency. On the morning of 21 July 1796, Burns died in Dumfries, at the age of 37.

As with many a great spirit, the events of his life give only a scant glimpse into the greatness of his mind. For one of almost no formal education to write outstanding poetry in the Scots language, a light Scots dialect, and standard English, shows a great fluency of tongue. Whether calling for social justice, celebrating Scottish heritage, expressing tender or sensual love, having a rollicking funny time, or waxing philosophical, Burns was always in command of his subject.

On that note, I come to the peroration of the piece, the poem that first stirred my love for all things Burns. In his title, Burns dates it to November 1785 (his age, 26). Late Autumn plowing of a field, he overturns and destroys a mouse nest. Despite the fact that Burns bore it no ill-will, the rodent scurried off in terror at the rude attack. Burns observes that, without a snug nest, the wee creature might not survive the winter. As with the natural poetic mind, Burns began to muse on deeper issues. In fact, his brother claimed that the poet composed the entire poem while still holding his plough.

Burns waxes poetic on the poor mouse’s plans and efforts to prepare for winter and how Burns has destroyed them all. In his usual sense of brotherhood and social contract, he says the mouse is welcome to the small amount of grain he steals and says:

I'm truly sorry man's dominion,

Has broken nature's social union,

An' justifies that ill opinion,

Which makes thee startle

At me, thy poor, earth-born companion,

An' fellow-mortal!

After lamenting with the mouse that foresight and preparation may be in vain, Burn’s coins the phase I quoted first about the plans of mice and men.

But Mousie, thou art no thy-lane,

In proving foresight may be vain:

The best laid schemes o’ Mice an’ Men

Gang aft agley,

An’ lea’e us nought but grief an’ pain,

For promis’d joy!

But he doesn’t leave it there. Recalling the travails of his family growing up and presaging the difficulties ahead of him in the only ten years of life left him, Burns envies the mouse:

Still thou art blest, compar'd wi' me

The present only toucheth thee:

But, Och! I backward cast my e'e.

On prospects drear!

An' forward, tho' I canna see,

I guess an' fear!

Rest well today, Rabbie. Though your flame burned only briefly, it burned bright and has lit many a soul in the years you’ve been gone.