-

Sign up or login, and you'll have full access to opportunities of forum.

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Judicial Corporal Punishment Of Women: Illustrations

- Thread starter elephas

- Start date

Harsh Martinet

Consul

Harsh Martinet

Consul

Harsh Martinet

Consul

Dafnees

Consul

I love this beautiful story. It remains me the tale of Justine of SadeThe final scene of a comic book adaptation of Cinderella - a public judicial flogging for the evil stepmother and stepsisters:

View attachment 902507

Full comic here (with various more domestic and semi-public floggings and canings):

Part 1

Part 2

Thanks a lot for sharing

nsur1

Governor

The final scene of a comic book adaptation of Cinderella - a public judicial flogging for the evil stepmother and stepsisters:

View attachment 902507

Full comic here (with various more domestic and semi-public floggings and canings):

Part 1

Part 2

Here is the subsequent panel showing stepmother and sisters (and evil servants) being banished from the Kingdom:

Which suggests to me that the artist is very well versed in the ancient German punishment of Staupenschlag, by which public flogging by the hangman was always combined with automatic banishment from the realm, as discussed in my post below in the "Stories and Novels" thread:

Thanks for those kind words. I am writing, but don't really want to post until I'm fairly sure I will be able to complete the story -- nothing worse than stories that are abandoned a couple of chapters in.

In the meantime, here is an interesting passage about Doris's punishment from a serious historical essay about the Katte process and the prince's desertion written in 1984 by the historian Gerd Heinrich:

View attachment 895027

"Grotesquely, the King appeared to consider that one of the co-conspirators in the "conspiracy" was Doris Elisabeth Ritter, a 16-year-old Postdam cantor's daughter whom the Crown Prince and Katte had occasionally paid harmless visits, merely crossing the boundaries of the court. [Actually, Katte did not know Doris -- Heinrich confuses him with Ingersleben.] She was arrested on 1 September, subjected to a virginity test which gave a negative result, and was on 7 September in accordance with an absurd punishment decision by the King, publically subjected to an outdated Staupenschlag by the hangman at several corners of Potsdam town centre and then delivered "for ever" to the Spinnhaus at Spandau. The equally innocent father, a native of Wurttemberg and a student of Francke, had to leave Potsdam, he hurriedly departed for the quieter Mecklenburg. Friedrich Wilhelm released the daughter only in mid-1733. This process also demonstrates the spells of mental instability and unreasonableness into which Friedrich Wilhelm lapsed over and over again during autumn of 1730, despite his demonstratively displayed jollity."

If Heinrich is right, the punishment meted out to Doris was considered even at the time to be wildly over the top compared to the supposed offence, and a sign of temporary insanity by the King.

The use of the word "Staupenschlag" here is interesting -- it does not appear in the King's actual order, but is clearly implicit in its wording. "Staupenschlag" is an ancient word in formal German judicial language which combines a public whipping with a formal loss of honour and expulsion from polite society. Here is the definition of the word from "Zedler's Univeral-Lexicon", published in 1744 (14 years after Doris's punishment), which we can assume reflects how her contemporaries understood Doris's punishment. Note just how long the dictionary entry is:

View attachment 895051

The German text reads (from here):

"Staupenschlag, ist, da der Verurtheilte öffentlich durch die Gassen und Strassen von dem Scharf-Richter, oder dessen Knecht, über die entblößten Schultern mit Ruthen gehauen wird. An theils Orten aber werden dergleichen Verbrecher an eine besonders darzu errichtete Staup-Säule, oder den Pranger, mit Händen und Füssen angebunden, und so von dem dabey stehenden Scharf-Richter, oder dessen Knechte, mit einer gewissen Anzahl Ruthen in die blossen Seiten und über den gantzen Rücken gestrichen. Bißweilen werden auch wohl in den Besen oder die Ruthen so gar, nach Beschaffenheit des Verbrechens, und zu desto empfindlichern Schmertzen, eiserne Dräter eingeflochten welches denn gemeiniglich auf den Tod hauen heißt; weil gar öffters die damit Gestäupte davon crepiren müssen. Sonst aber ist diese Art der Strafe heutiges Tages fast die gemeinste, und zugleich eine grosse und schwere Strafe, indem sie nicht nur sehr infamiret, sondern auch dem Leibe grosse Pein und Schmertzen verursachet. Worbey zu mercken, daß diese Strafe allezeit, die ewige Landesverweisung mit sich führet. Denn es wird keiner öffentlich mit Ruthen ausgestrichen, welcher nicht zugleich des Landes ewig verwiesen wird. Wenn der Delinquent schwach und kräncklich ist, also, daß er ohne Einbusse seines Lebens oder Gesundheit keinen starcken Staupenschlag vertragen kan, alsdann wird ein gelinder Staupenschlag dictiret. Wann dannenhero ein Weib ein säugend Kind hat, so ist die Aushauung mit Ruthen oder der Staupenschlag dergestalt zu moderiren, daß dem Kinde an seiner Nahrung kein Abbruch geschehen möge.

(...) Es pflegt wohl auch der Landes Herr solche Strafe bißweilen in Vestungsbau zu verwandeln. Und zwar entweder beydes, oder nur die Landesverweisung nach ausgestandenem Staupenschlage."

"Staupenschlag is when the condemned is publicly whipped with rods onto the bared shoulders [and driven] through the alleys and streets by the public hangman or his assistant. In some towns, such criminals are tied hand and foot to a whipping post or pillory specially erected for this purpose, and there beaten over the bared sides and the entire back with a certain number of lashes by the attending hangman, or his assistants. Sometimes, depending on the nature of the crime and to increase the pain, iron wires are bound into the bundle of switches or rods which is commonly referred to as "beating to death", as the thus whipped often die of their injuries. Either way, this type of punishment is these days almost the most common [or "the most vicious" -- "gemein" has two meanings and it is not clear which is intended here], and at the same time a grand and heavy penalty, as it is not only very dishonouring [and/or humiliating] but also causes great pain and agony to the body. It is to be noted that this punishment is invariably combined with permanent banishment for life, as nobody is publicly whipped who is not also banished from the lands. If the delinquent is weak and sickly so that they cannot suffer such a whipping without losing life or health, a milder whipping is carried out. If a woman has a suckling child, the whipping with rods is to be moderated so that the child's nourishment is not impaired.

(...) Sometimes, the ruler of the land may commute this penalty into imprisonment. This may apply to both elements, or only to the banishment after the completed Staupenschlag"

As can be seen from the passage about women with suckling babies, this type of punishment applied to men as well as women. The final sentence applies to Doris, who was sent to the Spinnhaus for life after the whipping rather than being banished from Prussia -- since the opening of the Spinnhaus at Spandau in 1682, the rulers or Prussia generally used imprisonment rather than banishment after public whippings, as they wanted to have a cheap source of labour to spin yarn for military uniforms. Doris may have preferred banishment, as her family had to flee from Prussia to Mecklenburg two days after her whipping anyway. However, banishment was in some places accompanied by either branding (with brands indicating the offence and the town from which the offender is banished, i.e. two separate brands) or mutilation (e.g. cutting off the ears) so that a returning convict can be recognised. That may not however have been in use in 18th century Prussia any more.

There are similar but less detailed entries for "Staupenschlag" in every 19th century German dictionary, a time when the punishment was obsolete but still in living memory. The details vary, but all entries stress the dishonouring and public nature of the penalty and the automatic combination with banishment for life. Some refer to whipping through the streets, some to whipping at a post or pillory, and one says that a whipping bench may be used instead of a post. As Germany had hundreds of separate jurisdictions at the time, I would expect this simply reflects local variations. Several refer to being beaten on the naked back, most mention bundles of switches, rods or birch twigs being used (but sometimes also rope or leather whips). Some refer to forty lashes being the standard punishment, based on an Old Testament verse (anybody here knows which one?). One refers to Staupenschlag being reserved specifically for the crimes of arson and whoring. Another says that Staupenschlag commonly involved a spell standing in the pillory, and may also have been combined with shearing of the hair.

I have however seen no references at all anywhere else for the use of multiple Staupenschlag punishments in a row, as for Doris, which would support that this was a cruel and unusual punishment in the eyes of the time, when even an ordinary Staupenschlag was a severe and life-threatening penalty even for hardened criminals. In view of the wording of the King's order, and of the above dictionary entry, it may be the case that rather than six separate whippings as seems to be the consensus among modern historians referring to her, what she actually got was a combination of two stationary whippings tied to the whipping post (one in front of the Town Hall and one in front of the school house where her father taught and lived) followed by whipping through the streets. How this works together with the "standard" forty lashes count is something I will need to figure out in writing my story.

For English speakers, this 1799 German-English dictionary gives several gory translations for Staupenschlag and the associated verb stäupen and participle ausgestäupt:

View attachment 895067

"The whip given by the hand of the Hangman or Executioner", "To be whipped or lashed by the Hangman's Hand; also to be whipped at the Whipping-Post", "to give the Whip, to lash, to scourge", "to whip till the Blood comes", "to be whipt at the Cart's Arse or Tail, to be flogg'd, to receive a Flogging at the Whipping-Post", "a Whipping, Lashing", "a Whip, a Spripe, Lash, Slash or Jerk with Rods".

elephas

Senator

elephas

Senator

#6 above is quite ominous...

elephas

Senator

Dafnees

Consul

I love this fat ass being whipped.

Thanks for sharing

nsur1

Governor

This is from "The Red Queens" by Hugdebert -- a comic book adaptation of the conflict between the Merowingian queens Brunhilda and Fredegund in the Frankish empire of the late sixth century AD. Surprisingly, it's historically reasonably accurate. This panel shows the reaction of Brunhilda when Fredegund sent her daughter to negotiate a peace.

The rest of the comic is here:

[Hugdebert] The Red Queens - E-Hentai Galleries

Free Hentai Western Gallery: [Hugdebert] The Red Queens - Tags: english, translated, hugdebert, daughter, mother, incest, comic, full color

e-hentai.org

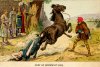

Brunhilda herself was eventually either torn apart by wild horses or dragged to death behind a wild horse (sources vary), as shown here first by Hugdebert and then (barely less luridly) in various historical prints -- a favourite subject of French illustrators over the years:

nsur1

Governor

Brunhilda herself was eventually either torn apart by wild horses or dragged to death behind a wild horse (sources vary), as shown here first by Hugdebert and then (barely less luridly) in various historical prints -- a favourite subject of French illustrators over the years:

Drifting a bit off-topic in this thread (although not on CF), I was intrigued by just how many old illustrations there are of Brunhilda's ("Brunehaut" in French) execution by wild horses, right back to medieval manuscripts. Here are a few late medieval ones -- it's notable that they tended to go with the "torn apart by horses" version rather than the "dragged behind a wild horse" one that the romantic artists preferred. Very variable degrees of realism. I like #3 with its fully-clothed dignified queen tied incongruously to the tail of a horse:

For comparison, one more 19th century version I found -- the only one I've seen that makes some allowance to the fact that Brunhilda was around 70 years old when she was executed: