[Continued from previous post]

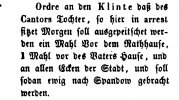

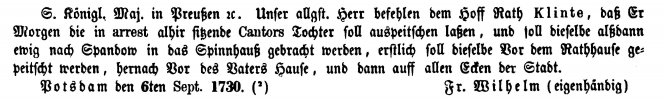

It is now 6 September and we are approaching the day of reckoning for Doris. She is still sitting in a custody cell at the Town Hall, where she has been since her arrest six days earlier, on 1 September. The King's hand-written order for her flogging and subsequent incarceration has been sent to the Mayor of Potsdam, the Privy Councillor Nicolaus Dietrich Klinte. The Town Hall was just across the Old Market square from the palace, and hence the order would have been received by Klinte with minimal delay the same day.

Let's consider for a moment what Klinte's role here is. Since a reorganisation of Potsdam local government in 1722, the post of civic mayor in charge of town administration and policing matters had been combined with that of the justice of the peace, presiding over all criminal and civic court cases. This powerful municipal post was held from 1722 to 1742 by Nicolaus Dietrich Klinte. In principle, he was supposed to rule the town in total autonomy. In practice, being in charge of the residence town of an absolute monarch with a history of issuing summary orders and micro management, which was also a garrison town with more than a third of residents being soldiers and therefore under military jurisdiction, his scope for independent action was rather more limited.

In the case of Doris Ritter, Klinte was in an impossible position. There is no doubt that he would have known her father, Matthias Ritter, very well indeed -- St. Nikolai, where Ritter was cantor, was the town's principal Lutheran church and was situated directly opposite Klinte's town hall. The grammar school affiliated to St. Nikolai, where Ritter was the rector (head master) and where his lodgings were, was also opposite the church, in the next building but one along from the Town Hall. If Klinte had any sons, they may well have been educated in Ritter's school. If Doris was indeed regularly singing solo parts at mass, Klinte would have seen her in church every week. According to the Röhrig book, Matthias Ritter was an avid social climber and networker, so in all likelihood Klinte would have met Doris at social and civic events in town on a regular basis. For the King, this was just some random commoner wench who had jumped into bed with a prince and had to be put in her place, but to Klinte this was the highly-respectable daughter of one of the town's leading citizens, poorly-paid perhaps but prominent and very well-connected. But however sympathetic Klinte was, as a Prussian official appointed by and reporting to the King, there was little he could do.

For the past six days, Doris had been sitting under Klinte's charge in one of the Town Hall custody cells (probably one of the holding cells for middle class prisoners rather than the dungeon for the common rabble -- Prussian town halls at the time observed class distinctions in their holding cells), but with an additional military guard posted who was outside Klinte's command. Klinte may have hoped that his dilemma would go away and Doris would be released once the King was satisfied that Doris played no role in the Prince's desertion plans and her interactions with the Prince were innocuous.

Receiving the King's cabinet order of 6 September dashed any such hopes. Klinte's judicial authority and civic autonomy were crudely overruled by the monarch's summary justice, and Klinte reduced to mere executor. He was to have the girl flogged in the most public and dramatic manner, and then sent to life incarceration in a workhouse intended for common scum. The impact of that order on the cream of Potsdam civic society would have been immediate and dramatic -- the daughter of one of their own was to be dishonoured. Could anything be done to stop this outrage at the eleventh hour? Klinte himself could not intervene, as he was in charge of administering the King's verdict, but that didn't stop him from being involved in a panicky last-minute attempt at lobbying anybody who might have any sort of influence with the King to try to change his mind.

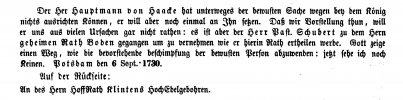

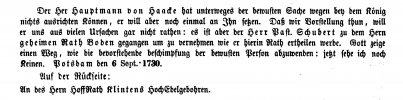

The above is not just idle speculation, but recorded in our next contemporaneous document, an utterly remarkable find preserved in the Potsdam Town Archives at least until 1869 when it was transcribed for the magazine of the Potsdam Historical Society:

5) Letter from Preacher Schultze of the Church of St. Nikolai to Mayor Klinte, dated 6 September 1730

"The Commandant von Haacke was not able to achieve anything with the King in the said matter, but he will try the get to Him once again. He strongly advises us against seeking an audience ourselves, for many reasons; however, Pastor Schubert has gone to see Councillor Boden to consult him for any advice he might give. May God show us a way as to how the imminent shaming of the subject person may yet to be averted : at this time I do not yet see one.

"The Commandant von Haacke was not able to achieve anything with the King in the said matter, but he will try the get to Him once again. He strongly advises us against seeking an audience ourselves, for many reasons; however, Pastor Schubert has gone to see Councillor Boden to consult him for any advice he might give. May God show us a way as to how the imminent shaming of the subject person may yet to be averted : at this time I do not yet see one.

Potsdam, the 6th of September 1730

On the reverse:

To Privy Councillor Klinte, Esq."

So, this is a letter from Schultze, the most senior church official in Potsdam, preacher and intendant of St. Nikolai (and hence the immediate superior of Matthias Ritter), to Klinte, the most senior civic offical and magistrate in Potsdam. In it, Schultze summarises concerted efforts by three further senior officials to try to change this King's mind:

- Hans Christoph Friedrich von Hacke (sometime spelled "Haacke") was the chief military adminstrator of Potsdam and hence in charge of military justice. Possibly more importantly, he was also a member of the King's famous "tobacco cabinet", the group of senior-advisors-cum-drinking-buddies with whom the King met every night for a session of smoking and drinking during which foreign and domestic affairs were discussed and decisions were made in an informal round with no protocol and no distinctions of rank, including for the King.

- Heinrich Schubert (1692-1757) was the pastor of the other main church in Potsdam, the Heilig-Geist-Kirche (Church of the Holy Spirit), and hence the second most senior Lutheran cleric in town, after Schultze.

- August Friedrich von Boden was a senior official in the King's government, in effect minister of finance, and also the King's personal cabinet secretary.

So, these were very heavyweight supporters trying to save Doris -- two of them have Wikipedia entries! -- demonstrating not only that Doris wasn't the lowly commoner wench usually depicted, but also that the King's order was seen as a screaming injustice even at the time. Also noteworthy that her supporters included the two men who should really be in charge of enforcing the laws on morality as well as civic and military justice. Klinte would have been resonsible for policing immoral conduct of the townspeople, whereas Hacke was responsible for enforcing military regulations amongst the soldiery in the garrison of Potsdam, including those on immoral conduct and suppressing prostitution.

However, all of them were helpless -- the King's mind was not to be changed and the following day, 7 September, the verdict was duly executed. We don't have any records of how precisely this was done, other than what it says in the King's order: she was to be flogged first in front of the Town Hall, then in front of her father's house, then "at all corners of the town", whatever that means.

It would have fallen to Klinte to pass the King's order to the town's hangman for execution, and to the hangman to make the logistical arrangements as to how and where and with what implement Doris was to be whipped. In this respect, there are three glaring omissions in the order: we don't know how many separate whipping sessions (at least two, plus unspecified further ones at "all corners"), how many lashes at each session or in total, and -- possibly most surprising at all -- what she was actually being punished for.

If you think about this, this last one is pretty strange. The whole point of a public flogging is to demonstrate justice being done in front of the populace: the delinquent's crimes are exposed and publically punished. They come with a public pronouncement of the crime and the sentence, prior to execution. So, what would Klinte have told the town crier to announce in the case of Doris? "You may have seen this girl before in church, and now it's the King's pleasure to have her stripped and whipped in front of you for no good reason at all" doesn't really work. She would either have to be publically declared to be a harlot and flogged for immorality, or as an accomplice in the Crown Prince's plot and flogged for conspiracy to desertion (which was actually a capital offence, although that was not inconsistently enforced). Realistically, with the Prince and Katte still under arrest and being interrogated pending court martial, and with the King still investigating possible other co-conspirators, the latter option would have been politically far to sensitive at the time, so I think there is little doubt that the public announcement on the market square prior to her first flogging, and then each subsequent flogging, would have been as a proven whore and harlot being punished by the hangman for immoral conduct at the command of the King.

That, of course, would have immediately dishonoured her and removed any class privileges in her treatment that she had previously enjoyed. No more middle-class holding cells at the Town Hall, no more formal questioning by (possibly) respectful officers addressing her in a polite way, no more protection by powerful supporters like Mayor Klinte. Just a bloody back and a half-dead traumatised girl being dragged from whipping post to whipping post, and through all parts of town in a neverending ordeal, immediately followed by delivery to Spandau as a lowly whore, to be incarcerated for the rest of her natural life.

There is no documentary record or witness account of any of this in the surviving records, but we can get a sense of place from old paintings of Potsdam. Here are two (one of them I had posted before), each showing the church of St Nikolai and the Town Hall opposite it, as well as the school building where Doris's father taught and where the family lived.

In both paintings, the town hall is at very right-hand edge of the frame (only seen partially in the first painting). This is where Doris sat in her cell for six days, where she was interrogated by Captain von Roeder and Ensign von Perband on 1 September, and in front of which she then received her first flogging on 7 September. The next-but-one building to the left of the Town Hall is the school. This is where Doris opened the door to the Prince, without recognising him (Ingersleben loitering by the church on the opposite side of the street), where she was arrested on 1 September, where v. Roeder and v. Perband searched her belongings and questioned her parents. Now, on 7 September, her first flogging completed, she was dragged along the street from the Town Hall to the school building, and flogged again in front of that house, followed by unknown further ordeals.

Here, the documentary trail picks up again. We do know that the entire punishment was indeed completed in a single day, on 7 September, following which we have a heart-breaking file notice added to the King's order as preserved in the Potsdam Town Archive, presumably in Klinte's own hand:

6) File notice on completion of execution, 7 September:

"On the 7th, execution took place and the verdict announced to the parents, of which the father is the rector, as well as to the delinquent Dorothea Elisabeth Ritter".

"On the 7th, execution took place and the verdict announced to the parents, of which the father is the rector, as well as to the delinquent Dorothea Elisabeth Ritter".

So, it fell to Klinte, despite his frantic efforts of the previous night, to go up to Doris and then to her parents to formally pronounce judgment and inform them of the penalty to be executed. Note that unlike the King's order, the file notice took great care to include Doris's actual name, and to refer to her father as the "rector" rather than "cantor" (not sure if Klinte wanted to make a point here).

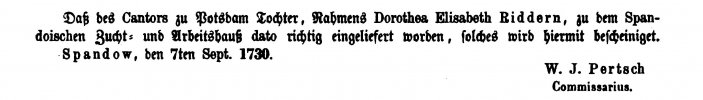

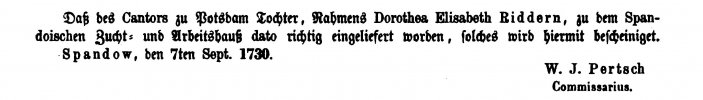

Completing this strand of the documentation, we get yet another administrative record -- Prussia's fame in respect of administrative order and bureacratic record keeping is well-deserved. This is the receipt issued by the Spinnhaus at Spandau when Doris was delivered to them, still on the same day, 7 September:

7) Receipt of the admission of the prisoner Dorothea Ritter at Spandau:

"That the daughter of the cantor at Potsdam, by name Dorothea Elisabeth Riddern, has been properly admitted to the prison and work house at Spandau, is hereby certified.

"That the daughter of the cantor at Potsdam, by name Dorothea Elisabeth Riddern, has been properly admitted to the prison and work house at Spandau, is hereby certified.

Spandau, the 7th of September 1730

Signed: W.J. Pertsch, Commissarius"

We don't know in what state she was on delivery, but we can guess -- the end of the worst day of her life, or anybody else's!

No doubt, there would have had to be some recuperation before she was in a fit state to work, but then the reality of the endless slog of 12-14 hours at the spinning wheel, exposed to random physical and (probably) sexual abuse by the wardens and prison officials would have materialised, with no prospect of ever being released. As a dishonoured whore having been publically flogged, she would have been fair game with no legal repercussions for any abusers.

Bringing this strand of the documentation to an end, now that his daughter had been dishonoured, the father's position in his Royal appointment and in polite Potsdam society could also no longer be maintained. Two days later, 9 September 1730, he was summarily dismissed from his post and fled the town as well as the country of Prussia, eventually scraping a position in Mecklenburg.

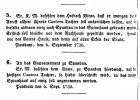

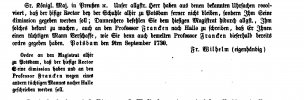

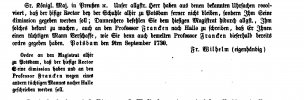

8) Cabinet order by His Majesty King Friedrich Wilhelm I of 9 September 1730, dismissal of Matthias Ritter:

As with the order for Doris's punishment, there are again two versions: the King's handwritten order in unadorned language and the more pompous official wording faired up by his secretary for the records. The King's own words are:

"Order to the magistrate here in Potsdam, that the rector here is to be dismissed and that a letter shall be sent to Professor Francke in Halle for another suitable man."

Or in faired-up language:

"His Royal Majesty in Prussia etc. Our gracious Lord has for the known reasons decided that the rector here of the school here at Potsdam is to be dismissed; Therefore direct the magistrate herewith to make this known to him, and also to write to Professor Francke at Halle that he shall send you a suitable man, as you have already sent order to Professor Francke to that effect.

Potsdam, the 9th September 1730"

That is a good point to pause, with Doris in the Spinnhouse recuperating from her wounds, and her Father, Mother and three little sisters frantically packing up to flee town and rebuild their lives.

It is not yet the end of the archive records, though -- I have still promised you the available evidence on the virginity test and the music-making. That's for the next installment.

[To be continued...]